On the Occasion of the Opening of Shadow and Light at McKinley Foundation (April 13, 2023)

In John Williams’ quietly magnificent 1965 campus novel Stoner, there’s an early scene in which the protagonist William Stoner is in graduate school. Stoner, a Missouri farm boy who had gone to college to study agriculture before being enchanted by literature, has fallen in love with learning and the life of the mind.

Sometimes, immersed in his books, there would come to him the awareness of all that he did not know, of all that he had not read; and the serenity for which he labored was shattered as he realized the little time he had in life to read so much, to learn what he had to know (Williams, Stoner, 26).

When I read Stoner a decade or so ago, I recognized parts of myself in William Stoner. Although my parents were college educated, I had no immediate role models growing up in my small hometown for the sort of immersive intellectual labors demanded by academic life. The closest models I had were the wacky, eccentric, sometimes mad, professors in the comic books I read and grew up to study.

Yet, in the back of my mind, I carried this image of faculty and academic life as being something like William Stoner imagined: an immersion in books, exploring and thinking about problems, both intangible and material. In moments, I still have that fantasy but it’s regularly driven off by incoming emails, a parade of course management systems, publication metrics, fiscal exigencies, and, increasingly, legislative and administrative concerns.

Those legislative and administrative concerns have focused almost solely on issues of academic freedom. Academic freedom is often likened to the First Amendment, and while the free speech principle unites them, they aren’t the same. The American Association of University Professor’s (AAUP) 1940 Statement on Principles of Academic Freedom and Tenure says,

Institutions of higher education are conducted for the common good and not to further the interest of either the individual teacher or the institution as a whole. The common good depends upon the free search for truth and its free exposition.

Vis-à-vis this articulation, the AAUP—the national organization at the forefront of academic freedom and other faculty issues—proposes four components: teaching, research, intramural speech, and extramural speech. In each of these areas, faculty should have the ability to speak and write freely, within boundaries of ethical, professional, and collective norms.

Across the United States, academic freedom is under threat. Florida’s Stop WOKE Act is perhaps the most egregious example. Although a court injunction is currently standing in the way of its implementation at colleges and universities, the Stop WOKE Act has as its aim to restrict particular viewpoints on race, gender, and sexuality. Faculty who express viewpoints—in teaching, research, and intramural or extramural speech— that oppose those espoused by the Florida government are at risk of being fired. Another Florida bill currently under consideration would eliminate university programs in women and gender studies, African American studies, and similar disciplines.

Though Florida is the most highly visible example, it is not alone. Between January 2021 and June 2022, at least seventy bills were considered by twenty-eight state legislatures in the US that would somehow impinge on academic freedom. Gag orders related to academic freedom in higher education were passed in Mississippi, South Dakota, and Tennessee. In Illinois, a 2022 bill that was not adopted would have restricted faculties’ abilities to teach about race, sex, and gender.

And it’s not just educational gag orders: faculty tenure is also under threat. In Kansas and Wisconsin, tenure has been reshaped, allowing state boards—not universities—to rescind tenure as needed under the guise of financial exigency. In Republican-led states such as Texas and North Dakota, efforts are being made to eliminate tenure and the academic freedom protections it affords. Nearby in Iowa, Republicans have unsuccessfully sought to alter tenure, but have not given up on the idea.

Tenure, long considered a safeguard for academic freedom, has already eroded substantially. At present, more than 70% of faculty in the United States are contingent. That means they are work for hire, adjuncts, precarious. Often this means they have few, if any protections regarding academic freedom, let alone living wages and health insurance.

Just last fall, an adjunct art history instructor was not re-appointed following a controversy in which she displayed a single image of the Prophet Muhammed. Despite the fact that the faculty member provided advance warnings to students—an indication to me of an ethic of care—Hamline’s president invoked the University’s civility statement, suggesting that in this instance, academic freedom had not been sufficiently balanced with the need to prevent harm.

On a more personal note, my biggest education regarding academic freedom took place here at UIUC in 2014. That was the year that Steven Salaita was hired to teach in the American Indian Studies program but was un-hired by campus administrators and the Board of Trustees shortly before the start of classes.. I was one of the faculty who fought for Salaita’s reinstatement. I gathered news and resources, helped run a Facebook page and Twitter feed with relevant information, attended Trustees’ meetings, and protested on campus.. From an improperly redacted set of campus documents, I publicly identified the name of the donor who was instrumental in pressuring the University to un-hire Salaita.

I fended off countless Twitter trolls, including the comedian Roseanne Barr. They accused me of being anti-Semitic, a libtard, an advocate for free speech and academic freedom only when it benefited my political viewpoints. I was called names that I choose not to repeat here. My choice to advocate for Salaita even alienated me from some of my departmental colleagues, who did not want to be involved or saw Salaita’s extramural speech on Twitter as lacking in civility and falling outside the bounds of academic freedom.

The AAUP’s investigatory body concurred that Salaita’s un-hiring was indeed an issue of academic freedom. Consequently, UIUC was placed on its list of censured institutions for two years. The lifting of censure in 2017 was not unanimous. But the damage was already done. The last I heard, Steven Salaita was driving a school bus, unable to obtain another tenure-track position. Here on campus, several members of the small program in American Indian Studies moved to faculty positions elsewhere.

All of this ground may seem like a too-long prelude to why we’re here this evening: to open the exhibit, Shadow and Light: Honoring Iraqi Academics. Between 2003 and 2012, years roughly coinciding with the US invasion and occupation of Iraq in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, hundreds of Iraqi scholars were slaughtered in bombings, shootings, and other attacks, both sectarian and by US troops.

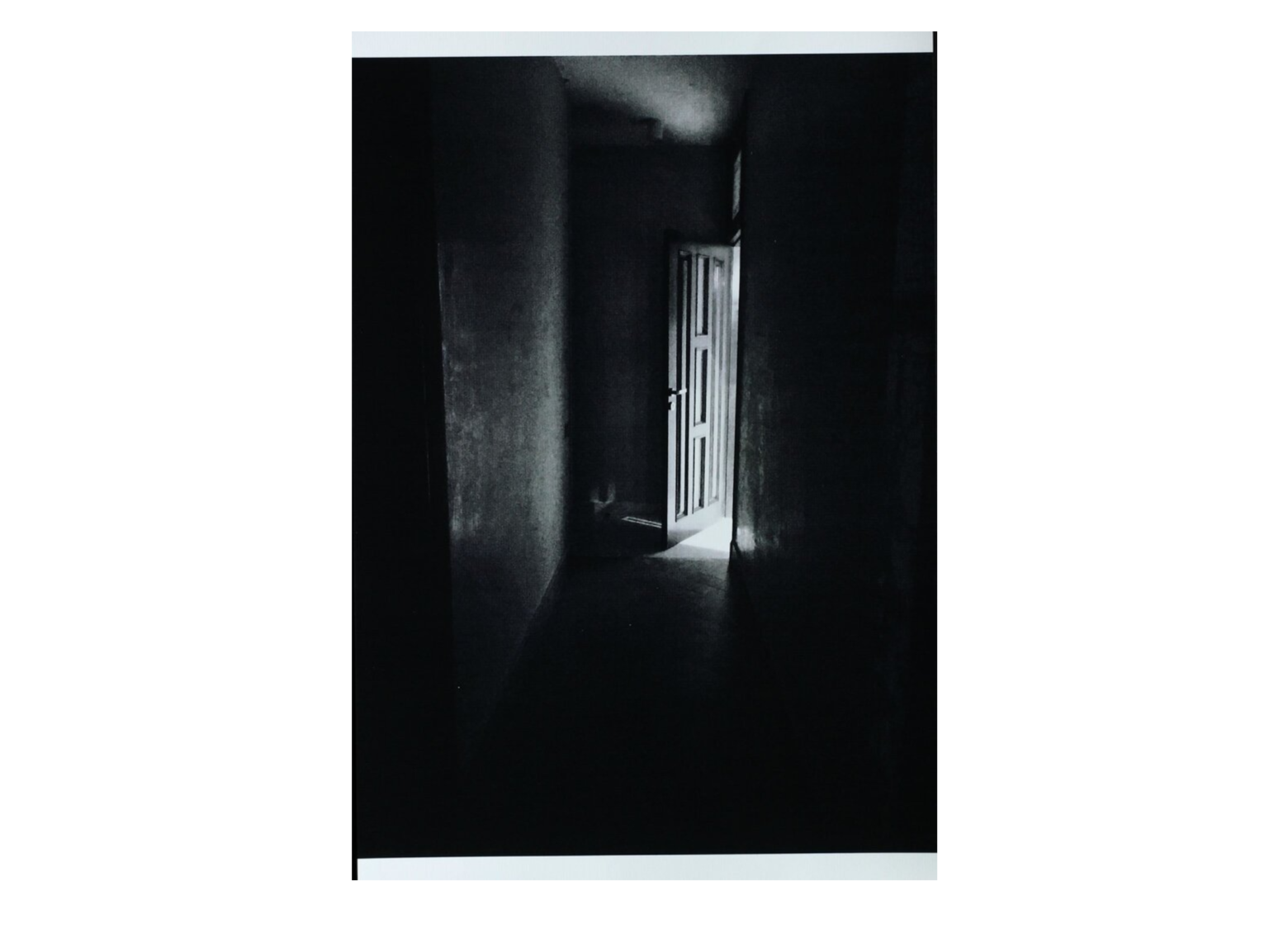

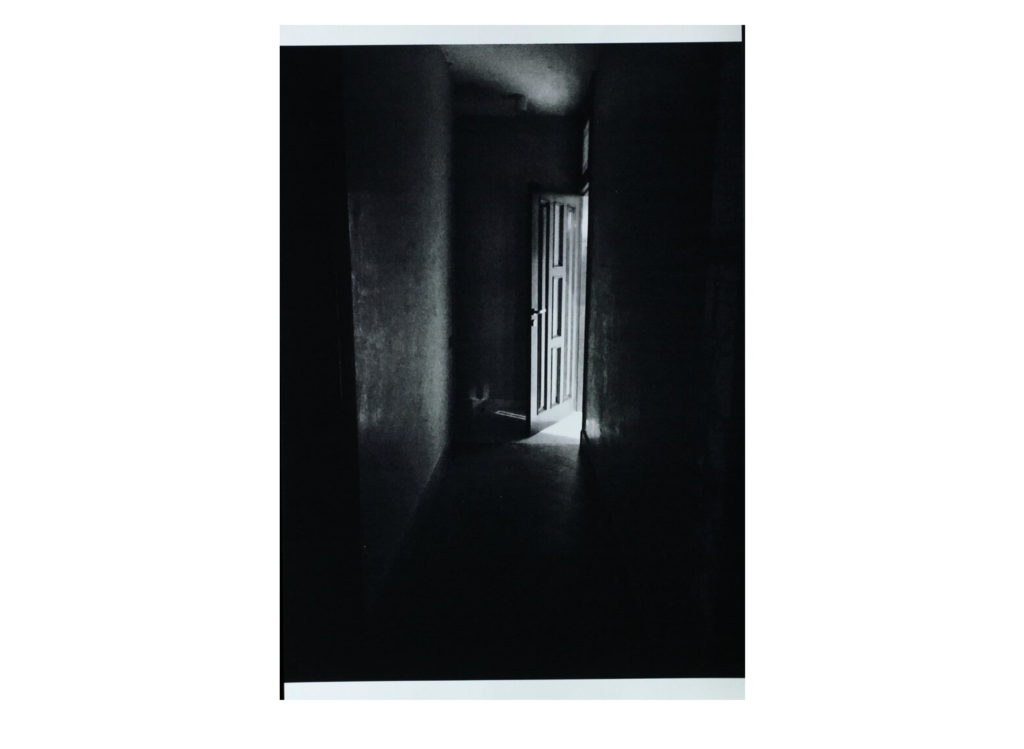

Photograph by Fatima El-Kalay from the exhibit Shadow and Light. This photograph honors a lecturer at Bagdad University of Technology who was killed on June 27, 2006. El-Kalay writes, “It’s safe to / cast away / the shadows /and enter the light.”

The website B Russell Tribunal, which draws its name from the 1960s anti-war tribunals led by philosopher Bertrand Russell, lists 479 Iraqi academics killed between 2003 and 2014. These 479 individuals held PhDs, MDs, and other advanced degrees. They taught in fields including law, medicine, agriculture, engineering, literature, history, psychology, fine arts, veterinary medicine, physics, and education. They were killed at home, on the way to work, at work, leaving mosques. Some were killed after being kidnapped and tortured.

Through photographs and statements, this exhibit attempts to draw connections between our lives here in the US and those that were lost more than 6,000 miles away. We never see the faces of these Iraqi academics, we don’t learn much about most of them. Their existences are almost ephemeral. Photography—that is, the ephemerality of light captured through the lens of a camera—seems a fitting medium for this exhibit. But please understand, these individuals were anything but ephemeral. They existed, they mattered. They had families and friends.

This exhibit also serves to draw connections between the knowledge these academics pursued and the knowledge their deaths deprived us of. And that’s where the issue of academic freedom enters. Death—unexpected, violently imposed, politically-motivated—is, after all, the greatest assault on academic freedom.

Although the focus of this exhibit is more than a decade in the past, scholars and students in Iraq still face challenges around academic freedom. Scholars at Risk, a global organization that monitors academic freedom globally and works to provide sanctuary to threatened scholars, reports several incidents in Iraq during the last year and a half. While no deaths were reported, both faculty and students at several universities were beaten and tear-gassed for protesting university fees and policies.

Scholars at Risk has worked in conjunction with researchers from other organizations to build the Academic Freedom Index. This index has, since 2017, provided expert analyses of the state of academic freedom globally. It attempts to measure factors such as freedom to research and teach, campus integrity, and freedom of artistic and cultural expression at national levels. The Index uses a scale from 0 to 1, with zero conceptualizing a complete lack of academic freedom, and 1 as robust protection. Iraq’s 2022 score is 0.46, essentially the same as it was during the period this exhibit addresses.

While I do not want to minimize the struggles facing Iraqi scholars and students, I want to acknowledge that scholars working in so many other countries around the world experience significant assaults on their academic freedom. Countries including Iran, Turkey, Syria, Myanmar, Egypt, Nicaragua, Saudi Arabia, Equatorial Guinea, Belarus, and China all have current Academic Freedom Index scores below 0.10.

Here in the US, our score is falling. While countries such as Germany, Nigeria, and Argentina have scores above 0.90, the US currently sits at 0.79. In 2019, our score was 0.91. Reductions in the freedoms to research and teach, along with campus integrity and institutional autonomy contributed most to the decline. The examples with which I opened this talk are having a profound chilling effect on academic freedom in this country.

As you look through the images in this exhibition and read the artists’ statements, I encourage you to take a moment to honor the memories of each of these academics. Commit yourself to ensuring that their deaths are not recapitulated in other locations. Get educated about ongoing threats to academic freedom and teacher autonomy in the US at not just the college level, but in K-12 schools too. Speak out against legislation that diminishes the professional authority of educators and librarians.

I am not so naive about life in academia as I once was. I still rejoice in the moments when I can lose myself in teaching and research, conversation and thought, just as William Stoner did in the novel. But I also know that there are battles to be fought, so I carry in my heart the admonition that Stoner’s mentor, a professor named Archer Sloane, gives him in the book. Sloane says,

You must remember what you are and what you have chosen to become, and the significance of what you are doing. There are wars and defeats and victories of the human race that are not military and that are not recorded in the annals of history. Remember that while you’re trying to decide what to do” (Williams, Stoner, 37).

Bibliography

American Association of Colleges and Universities (2022). Statement by AAC&U and Pen America Regarding Recent Legislative Restrictions on Teaching and Learning. June 8.

American Association of University Professors (1940). 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure.

American Association of University Professors (2018).Data Snapshot: Contingent Faculty in US Higher Education.

B Russells Tribunal (n.d.) List of Killed Iraqi Academics.

Flaherty, Colleen (2017). Off and On the Censure List. Inside Higher Education. June 18.

Hamline University (2023). Statements from Hamline University – January 2023 to Present.

2021 Illinois House Bill No. 505 (2022). Parental Access and Curriculum.

Murphy, Erin (2023). Tenure Ban Shelved Again, but More Reviews May Be Proposed. The Gazette. January 24.

PEN America (2022). America’s Censored Classrooms.

Salaita and Beyond: On Academic Freedom and Faculty Governance. Facebook Page.

Scholars at Risk Network (2023). Academic Freedom Monitoring Project.

Spannagel, Janika and Katrin Kinzelbach (2022). The Academic Freedom Index and Its Indicators. Introduction to New Global Time-Series V Dem Data. Quality & Quantity.

Tenure Stream Faculty of the University of Minnesota Art History Department (2023). Art History Faculty Statement on Recent Events at Hamline University

Villa, Jessica (2023). Handling of Art History Professor in ‘Islamophobic’ Incident Was a ‘Misstep,’ Hamline University Says. ArtNews. January 18.

Williams, John (1965, 2003). Stoner. New York Review of Books.