I am a former high school librarian. For more than twenty years I have taught graduate students who plan to work with young people in public and school libraries. I am also a historian who studies the intersection of comics, young readers, and libraries in the US during the mid-20th century. Unsurprisingly the recent surge in challenges to materials in schools and public libraries across the United States has piqued my interest.

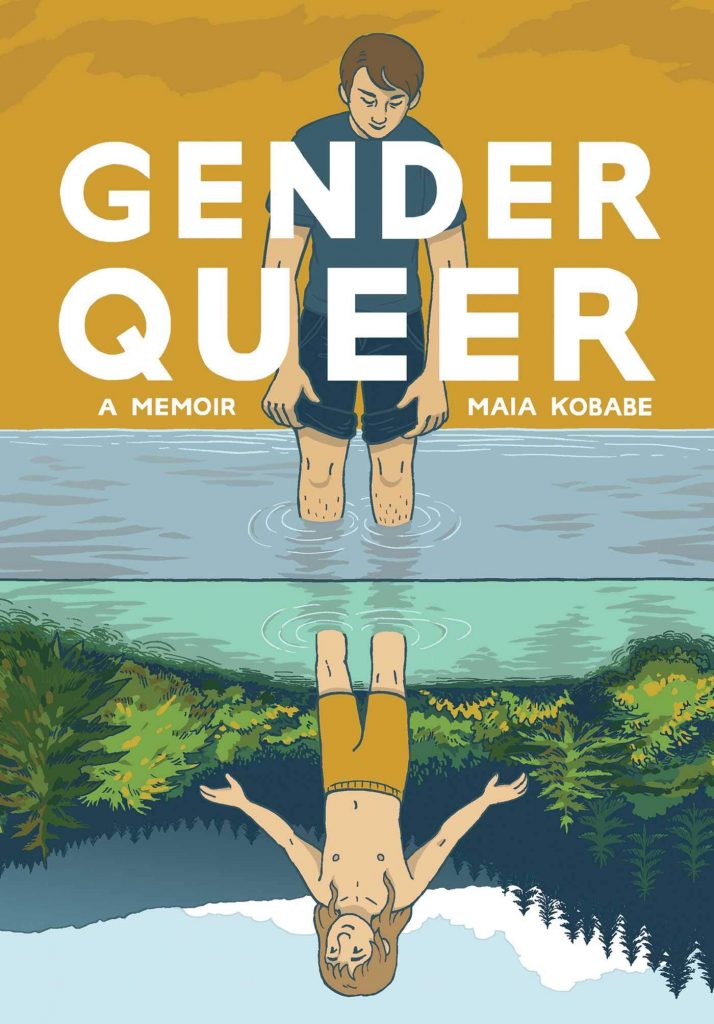

Adults are questioning whether graphic novels are suitable reading materials for young people. Scrutinized titles include Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer: A Memoir, Jerry Craft’s New Kid, Cathy G. Johnson’s The Breakaways, and Mariko and Jillian Tamaki’s This One Summer. Whether in Texas, Virginia, Alaska, Florida, or even here in Illinois, challengers commonly cite sexual explicitness and the perpetuation of Critical Race Theory or other divisive ideas as factors leading to their requests to remove these books from circulation. A trustee for Michigan’s Kent District Libraries spoke more plainly about Ngozi Ukazu’s Check, Please!. According to a report by Michigan’s WOOD-TV, he railed, “That right there, ‘Check, Please,’ is trash…Tax dollars are providing trash.”

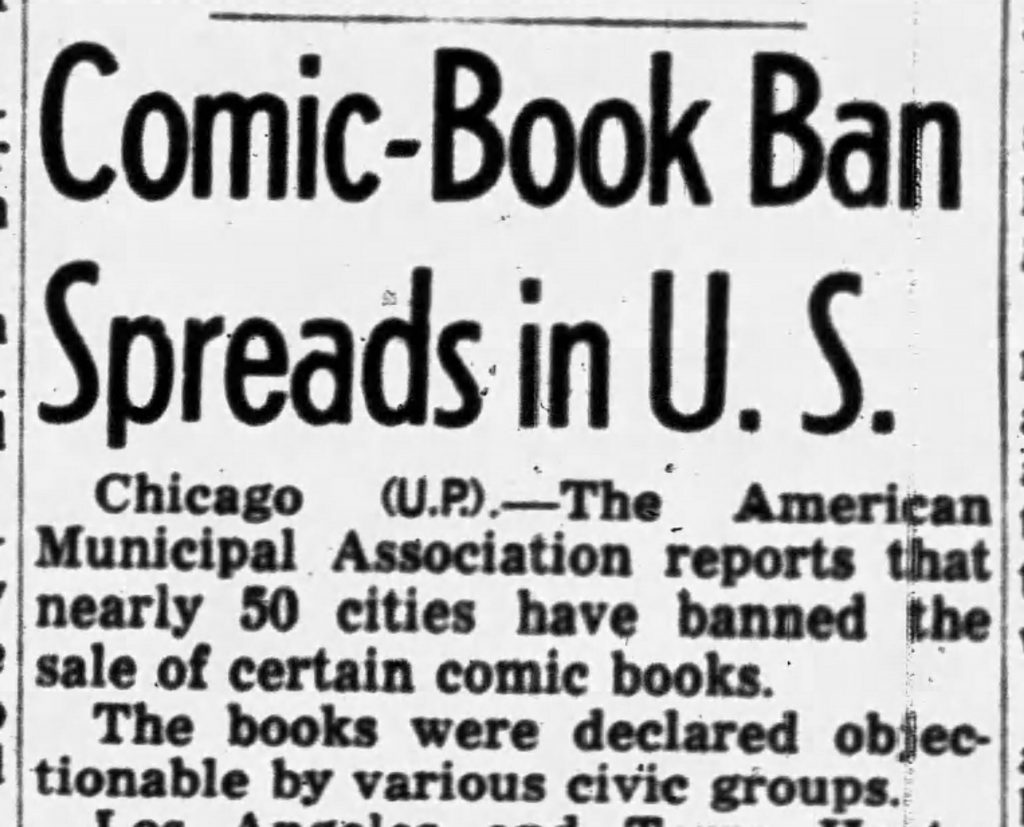

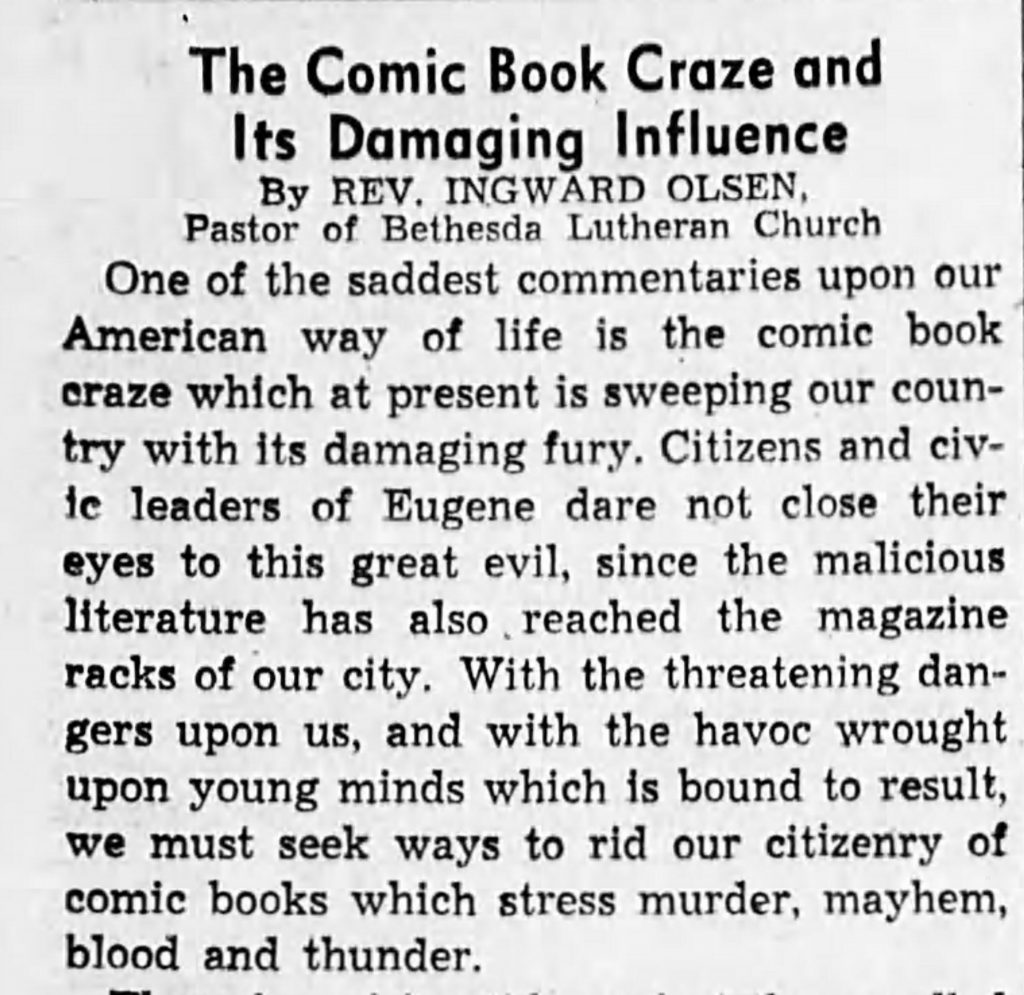

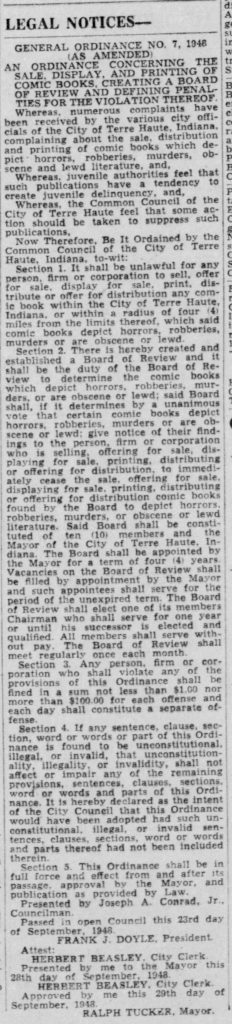

As I think about this current wave of book challenges, I cannot help but remember we’ve been here before with comics. In 1948, angry parent groups, religious leaders, and politicians held forth in raucous town halls across the country. Local municipalities and some states discussed and enacted ordinances and legislation restricting comics sales and distribution. Newspapers ran op-eds condemning comic books and their publishers. Had libraries collected or schools used comics at that time (there are examples of both, but they tend to have been more sporadic than pervasive), the battles against comic books would have erupted there as well.

(To be fair, some young people – perhaps motivated by adult discourse around comics or because of genuinely held beliefs – participated in anti-comics work in 1948. For example, a Boy Scout troop in Freeport, Illinois, decided to burn their comics “when they read a newspaper story which described the torture of one little boy by three others,” supposedly motivated by ideas found in comics.The Freeport Journal-Standard, 30 August 1948 issue has more information.)

Beyond the superficial similarities between the events of 1948 and those happening today, I see deeper resonances.

First, both then and now comics were experiencing enormous growth in sales and readership, especially among children and teens. In 1948, annual comic book sales exceeded an estimated 700 million issues, about five comic books for every person living then in the US. That was a seven-fold growth from 1940 with children and teens propelling that increase. Similarly graphic novels and manga—comic books’ contemporary descendants—are experiencing enormous growth. As reported recently in Publishers Weekly, sales of print and digital comics in North America reached nearly $1.3 billion dollars in 2020, with younger readers spurring much of it. In many school and public libraries, comics are among the highest circulating items.

Adults in 1948 and those today worry about the company their children keep in comics, graphic novels, and other books. In Maia Kobabe’s October 29th essay for the Washington Post about finding eir comic Gender Queer: A Memoir at the center of the spate of current book challenges, Kobabe recounts the “books [that] kept me company through my years of questioning and confusion.” Comics can be companions and confidants, guides to other worlds and ways of thinking. And with their visual content, comics can make those alternative worlds and new ideas more tangible and alive.

Second, comics and graphic novels are bogeymen. In 1948, many adults feared that reading comics would lead children and teens to become corrupted, seduced, made violent, sexually perverse, and un-American. Moreover, moments spent reading are not necessarily moments spent with family or being socialized into family norms. Today, that argument—especially the parts around sexuality and citizenship—remains a vivid undercurrent in the debates around what comics and other books young people should be permitted to read.

Yet, in both instances, these arguments aren’t what they seem. In the wake of World War II, people around the US grappled with new normalcies in areas such as gender roles and family dynamics and civil rights for non-white citizens. Today we in the US face similar social and cultural reckonings. Questions about gender roles have become questions about gender identities; discourse around civil rights is now more focused on racism, equity, and full participation than on inclusion. These issues, whether in 1948 or 2021, do not make for easy conversations and some adults would rather maintain or revert the status quo rather than talk.

Some young people spoke out against adults’ attempts at restricting comics in 1948 and the years that followed. They spoke up at public fora, wrote to elected representatives, and kept on reading comics. I see the same drive among today’s youth, like the students in Downers Grove, Illinois, who recently spoke out for retaining Kobabe’s Gender Queer or those in York, Pennsylvania, who successfully fought a book ban there.

I empathize with adults and the fears that motivate some of their challenges to comics and other books, yet I stand with young people. Many of them want to have hard conversations and explore new ideas and identities. Comics and graphic novels can be springboards for just that.

Coda: Organizations like the National Coalition Against Censorship, Pen America, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, and the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom support efforts to maintain free and unfettered access to books and other materials in US schools and libraries. Other organizations such as the National Council of Teachers of English and Reading with Pictures provide guidance on teaching with comics and graphic novels.

Cite this post (APA): Tilley, C.L. (2021, November 29). Banning comics: It’s 1948 again. https://caroltilley.net/2021/11/banning-comics-its-1948-again/